61話 資産家ウパーリ ・・・・ ジャイナ教を捨てて

第5部 さまざまな「悪」

第4章 外道―異教徒たち

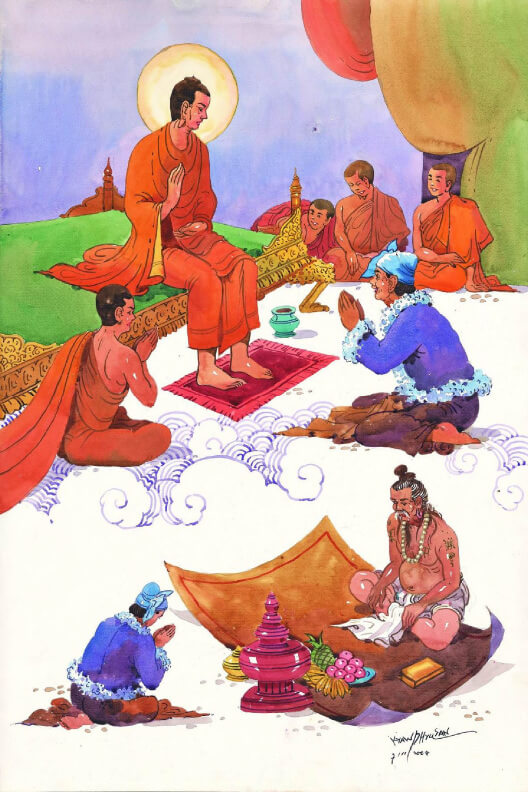

61話 資産家ウパーリ ・・・・ ジャイナ教を捨てて

ブッダの年代記のなかに「ウパーリ」という同じ名前の人物が二人いる。

一人目は理髪師ウパーリ。釈迦族の六人の王族青年(訳注:バッディヤ、アヌルッダ、アーナンダ、バグ、キンビラ、デーヴァダッタ)とともに、アヌピヤ・マンゴー林で、世尊のもとで出家して具足戒を受けた。かれは戒律に精通し(律受持(ヴィナヤダラ))、第一結集の律の誦出者に任命されている。

二人目はバーラカの長者で、ニガンタ・ナータプッタ(訳注:「六師外道」の一人でジャイナ教開祖)の卓越した弟子の一人である。かれは資産家ウパーリとして著名であった。世尊の説法を聴いた後、たいへん喜び、ただちに世尊の信者になりたい、という望みを表明した。以下は、その物語である。

あるとき、ニガンタ・ナータプッタが、ウパーリに率いられたバーラカの在家者のかなりの大会衆とともに坐っていたとき、ニガンタのディーガ・タパッシーがやってきた。ニガンタ・ナータプッタが、こう尋ねた。

「この真昼どきに、おまえはどこからやってきたのだ、タパッシーよ?」

「わたしはゴータマ沙門のいるところからやってきました、尊師よ」

「おまえはゴータマ沙門と何か会話したのか、タパッシーよ?」

「はい、わたしはゴータマ沙門と、それなりの会話をしました、尊師よ」

「かれとの会話とは、どんなものだったのか、タパッシーよ?」

それから、ニガンタのディーガ・タパッシーは、世尊との会話のすべてをニガンタ・ナータプッタに語った。

「けさ、ナーランダー(訳注:ラージャガハから1ヨージャナの距離で、5世紀から12世紀にかけてインド随一の学問寺があり、仏教教学の中心地として栄えた)で托鉢にまわって、わたしの布施食をいただいてから、パーヴァーリカのマンゴー林へ、わたしはゴータマ沙門に会うために行きました。わたしは、かれとあいさつを交わしました。礼儀正しい、和やかなあいさつの交換後、かれはわたしに、坐るように、といいました。それからかれは、こう尋ねました。

『タパッシーよ、ニガンタ・ナータプッタは、どれほどの種類、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の展開を説いていますか?』

『友、ゴータマよ、ニガンタ・ナータプッタは、〈行為、行為〉(業(カンマ))と、説く習わしがありません。ニガンタ・ナータプッタは、〈暴力、暴力〉(鞭(ダンダ))と、説く習わしがありません』

『それではタパッシーよ、ニガンタ・ナータプッタは、どれほどの種類、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の犯行を説いていますか?』

『友、ゴータマよ、ニガンタ・ナータプッタは、三種類の暴力を、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の犯行で説いています。すなわち、身体の暴力(身(カーヤ)の鞭(ダンダ))、言葉の暴力(語(ワチャー)の鞭(ダンダ))、精神の暴力(意(マノー)の鞭(ダンダ))です』

『タパッシーよ、このように分析され、分類されたこれら三種類の暴力、身体の暴力、言葉の暴力、精神の暴力で、ニガンタ・ナータプッタが、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の犯行で、もっとも非難されるべきものとして説いているのは、どれですか?』

『このように分析され、分類されたこれら三種類の暴力のうち、友、ゴータマよ、ニガンタ・ナータプッタは、身体の暴力(身(カーヤ)の鞭(ダンダ))を、もっとも非難されるべきものとして説いています。なぜなら、悪しき行為の犯行では、言葉の暴力、精神の暴力は、それほどでもないからです』

『そなたは、身体の暴力、といいましたか、タパッシーよ』

『わたしは、身体の暴力、といいました、友、ゴータマよ』

『そなたは、身体の暴力、といいましたか、タパッシーよ』

『わたしは、身体の暴力、といいました、友、ゴータマよ』

『そなたは、身体の暴力、といいましたか、タパッシーよ』

『わたしは、身体の暴力、といいました、友、ゴータマよ』

このように、尊師よ、ゴータマ沙門は尋ね、そして、わたしは三度まで同じ答えを続けました。それから、わたしはかれに、こう尋ねました。

『それでは友、ゴータマよ、あなたは、どれほどの種類、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の犯行を説いていますか?』

『タパッシーよ、如来(タターガタ)は〈暴力、暴力〉(鞭(ダンダ))と、説く習わしがありません。如来(タターガタ)は〈行為、行為〉(業(カンマ))と、説く習わしがありません』

『しかし、友、ゴータマよ、あなたは、どれほどの種類、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の犯行を説いていますか?』

『タパッシーよ、わたしは三種類の暴力を、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の犯行で説いています。すなわち、身体の暴力(身(カーヤ)の鞭(ダンダ))、言葉の暴力(語(ワチャー)の鞭(ダンダ))、精神の暴力(意(マノー)の鞭(ダンダ))です』

『このように分析され、分類されたこれら三種類の暴力、身体の暴力、言葉の暴力、精神の暴力で、友、ゴータマよ、あなたが、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の犯行で、もっとも非難されるべきものとして説いているのは、どれですか?』

『このように分析され、分類されたこれら三種類の暴力で、タパッシーよ、わたしが、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の犯行では、精神の暴力(意(マノー)の鞭(ダンダ))を、もっとも非難されるべきものとして説いています。そして、身体の暴力、言葉の暴力は、それほどでもありません』

『あなたは、精神の暴力、といいましたか、友、ゴータマよ』

『わたしは、精神の暴力、といいました、タパッシーよ』

『あなたは、精神の暴力、といいましたか、友、ゴータマよ』

『わたしは、精神の暴力、といいました、タパッシーよ』

このように、尊師よ、わたしはゴータマ沙門に三度まで同じ答えを続けさせました。それから、わたしは席を立ち、ここへきたのです、尊師よ」

これが語られたとき、ニガンタ・ナータプッタは、かれを称賛して、こういった。

「よろしい、よろしい、タパッシーよ! ニガンタのディーガ・タパッシーは、みずからの師の教えを正しく理解している、よく教育された弟子のように、ゴータマ沙門に答えた。どうして、些細な精神の暴力を、粗大な身体の暴力と比べて考えるのか? まったく逆で、身体の暴力は、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の犯行では、もっとも非難されるべきものであり、言葉の暴力と精神の暴力は、それほどでもない」

そのとき、会衆のなかに坐っていたウパーリは、ニガンタのディーガ・タパッシーの語る報告を注意深く聴いていた。かれもまた、ニガンタのディーガ・タパッシーを称賛し、ニガンタ・ナータプッタの面前で、こういった。

「さて尊師よ、わたしが行って、ゴータマ沙門の教義をこの報告にもとづいて論破してみせましょう。もし、ゴータマ沙門が、ニガンタのディーガ・タパッシーがつづけさせたような見解をわたしの面前で主張するなら、そのときは、力の強い男が長い毛をした羊のその毛をつかんで引きつけ、押し返し、引き回すように、いやそれよりさらに、わたしは論戦のなかでゴータマ沙門をつかんで引きつけ、押し返し、引き回すでしょう。尊師よ、わたしが行って、ゴータマ沙門の教義をこの報告にもとづいて論破してみせましょう」

そこで、ニガンタ・ナータプッタは、かれを駆りたてるように、こういった。

「行きなさい、資産家よ、そして、ゴータマ沙門の教義をこの報告にもとづいて論破してみせなさい。なぜなら、わたしか、ニガンタのディーガ・タパッシーか、あるいはそなた自身が、ゴータマ沙門の教義を論破すべきなのだから」

「わかりました、尊師よ」と、資産家ウパーリは答えた。その後、席から立ち上がった。ニガンタ・ナータプッタに敬礼後、右回りしながら去り、世尊のもとへ向かった。

さて、そのころ、世尊はナーランダーのパーヴァーリカ・マンゴー林に住まわれていたのだが、ニガンタ・ナータプッタの信者であるウパーリが、意思的行為(業)について論争するつもりでやって来たのだ。世尊に敬礼したあと、ウパーリは一方に坐って、こう尋ねた。

「尊師よ、ニガンタのディーガ・タパッシーは、ここへ来られましたか?」

「ニガンタのディーガ・タパッシーは、ここへ来ました、資産家よ」

「尊師よ、あなたはかれと何か話されましたか?」

「わたしは、かれと話しました、資産家よ」

「どのようなことを、あなたは、かれと話されましたか、尊師よ?」

そこで、世尊は資産家ウパーリに、ニガンタのディーガ・タパッシーと交わした会話のすべてを語られた。

それが語られると、資産家ウパーリは世尊に、こういった。

「すばらしい、すばらしい、尊師よ、タパッシーの部分は! ニガンタのディーガ・タパッシーは世尊に、みずからの師の教えを正しく理解している、よく教育された弟子のように答えています。どうして些細な精神の暴力を、粗大な身体の暴力と比べて考えるのでしょうか? まったく逆で、身体の暴力は、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の犯行では、もっとも非難されるべきものであり、言葉の暴力と精神の暴力は、それほどでもないのです」

「資産家よ、もし、そなたが真理にもとづいて議論しようとするのなら、われわれはこれについて会話できるかもしれません」

「わたしは真理にもとづいて議論しようと思います、尊師よ。だから、われわれはこれについて会話しましょう」

「そなたは、どう思いますか、資産家よ? ここで、ニガンタの信者が病気になり、苦しみ、そして、冷たい水の処方が必要な重病人になっているのに、かれの誓戒が冷水を拒むのです。かれは心ではそれを切望しているのに、冷水を拒絶するのです。そして、許容できる湯だけを使うかもしれません。かくして誓戒を身体的に、また、言葉でも守っているのです。かれは冷たい水が得られないために死んでしまうかもしれません。さて、資産家よ、ニガンタ・ナータプッタは、かれはどこに生まれ変わる、と説くのでしょうか?」

「尊師よ、〈意に縛られたものたち〉(マノーサッター神)という神々がいます。かれは、そこに生まれ変わります。それは、なぜか? かれが死ぬとき、かれはまだ、心のなかで束縛されたままだからです」

「資産家よ、資産家よ、そなたはどのように答えるのか、注意しなさい! そなたが前にいったことと、後でいったことは一致しておらず、後でいったことが、前にいったことと一致していません。しかも、そなたは『わたしは真理にもとづいて議論しようと思います、尊師よ。だから、われわれはこれについて会話しましょう』と、いっていたのです」

「尊師よ、世尊はそのように話されましたが、それでも身体の暴力は、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の犯行では、もっとも非難されるべきものであり、言葉の暴力と精神の暴力は、それほどでもないのです」

「そなたは、どう思いますか、資産家よ? ここで、ニガンタの信者は四種類からなる自己抑制で修練しているかもしれません。かれは、あらゆる水について抑制しています。すなわち、かれは、あらゆる悪の回避ができています。かれは、悪の回避によって浄化されています。そして、かれはあらゆる悪の回避にみちています。にもかかわらず、進みながら、そして退きながら、多くの小さな生き物を殺害するにいたるのです。どのような果報をニガンタ・ナータプッタは、かれ自身に説いているのですか?」

(訳注:ジャイナ教は、水中の微生物はじめ、あらゆる生きものの命を奪わない不害・不殺生=アヒンサーを徹底する苦行・禁欲主義で知られる)

「尊師よ、ニガンタ・ナータプッタは、故意ではないものは大いに非難されるべきだ、と説いていません」

「では、それが故意であるなら、どうなのですか、資産家よ?」

「そのときは、大いに非難されるべきです、尊師よ」

「では、三つの暴力のうち、ニガンタ・ナータプッタは、どれを意思と、説いているのですか、資産家よ?」

「精神の暴力です、尊師よ」

「資産家よ、資産家よ、そなたはどのように答えるのか、気をつけなさい! そなたが前にいったことと、後でいったことは一致しておらず、後でいったことが、前にいったことと一致していません。しかも、そなたは『わたしは真理にもとづいて議論しようと思います、尊師よ。だから、われわれはこれについて会話しましょう』と、いっていたのです」

「尊師よ、世尊はそのように話されましたが、それでも身体の暴力は、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の犯行では、もっとも非難されるべきものであり、言葉の暴力と精神の暴力は、それほどでもないのです」

「そなたは、どう思いますか、資産家よ? この街、ナーランダーは、繁栄し、富み栄えていますか? 人で混雑し、にぎわっていますか?」

「はい、そのとおりです、尊師よ」

「そなたは、どう思いますか、資産家よ? ここに抜き身の剣をふりかざした男が一人やって来て、このようにいうとしましょう。『一瞬のうちに、一須臾のうちに、俺がナーランダーのすべての生き物をひとつの肉の山、ひとつの肉のかたまりに、してみせよう』そなたは、どう思いますか、資産家よ、その男が、そうできるのかどうか?」

「尊師よ、十人、二十人、三十人、四十人、あるいは、たとえ五十人の男であっても、ナーランダーのすべての生き物を、一瞬のうちに、または一須臾のうちに、ひとつの肉の山、ひとつの肉のかたまりに、してみせる、などということはできません。ですから、たった一人の男がそうできる、などと考えられるでしょうか?」

「そなたは、どう思いますか、資産家よ? ここに神通力をもち、心の自在を得ている修行者かバラモンがやって来て、このように言うとしましょう。『我は、このナーランダーの街を、憎悪の意思作用ひとつで灰燼に帰してみせよう』そなたは、どう思いますか、資産家よ、そのような修行者かバラモンが、そうできるのかどうか?」

「尊師よ、そのような神通力をもち、心の自在を得ている一人の修行者かバラモンは、十、二十、三十、四十、あるいは、たとえ五十のナーランダーの街でも、憎悪の意思作用ひとつで灰燼に帰してみせることができます。ですから、たったひとつのナーランダーの街をそうできない、などと考えられるでしょうか?」

「資産家よ、資産家よ、そなたはどのように答えるのか、気をつけなさい! そなたが前にいったことと、後でいったことは一致しておらず、後でいったことが、前にいったことと一致していません。しかも、そなたは『わたしは真理にもとづいて議論しようと思います、尊師よ。だから、われわれはこれについて会話しましょう』と、言っていたのです」

「尊師よ、世尊はそのように話されましたが、それでも身体の暴力は、悪しき行為の実行と、悪しき行為の犯行では、もっとも非難されるべきものであり、言葉の暴力と精神の暴力は、それほどでもないのです」

「そなたは、どう思いますか、資産家よ? そなたは、ダンダキー、カーリンガ、メッジャ、そしてマータンガという森のみが森になっている、ということを聞いていますか?」

「はい、尊師よ」

「それを聞いているのであれば、どのようにしてそれらの森は、森になったのですか?」

「尊師よ、わたしは、仙人たちの一つの憎悪の意思作用によって森になった、と聞いています」

「資産家よ、資産家よ、そなたはどのように答えるのか、気をつけなさい! そなたが前にいったことと、後でいったことは一致しておらず、後でいったことが、前にいったことと一致していません。しかも、そなたは『わたしは真理にもとづいて議論しようと思います、尊師よ。だから、われわれはこれについて会話しましょう』と、いっていたのです」

「尊師よ、わたしは、世尊のまさに最初の喩えで満足して、喜んでいるのです。しかしながら、わたしは、世尊の問題へのさまざまな解答をおききしたくて、世尊に、このように反論しよう、と考えました。すばらしいことです、尊師よ! すばらしいことです、尊師よ! 世尊は真理(ダンマ)を多くのやり方で明らかにされました。まるで世尊は、倒れていたものを立ち上がらせるかのように、隠されていたものを暴露するかのように、道に迷った者に道を示すかのように、あるいは、もろもろのもののかたちが見える視力をそなえた者たちのために、暗闇で灯りを高く掲げるかのように。尊師よ、わたしは世尊と真理(ダンマ)と僧団(サンガ)(三宝)に帰依いたします。世尊がわたしを生涯帰依する在家の信者として、お認めくださいますように」

「徹底的に調べてみなさい、資産家よ! そなたのように著名な人は、まず、徹底的に調べてみることがよいのです」

ウパーリは世尊の思いがけない発言に大喜びした。かれは、こういった。

「尊師よ、わたしが異教徒の弟子になったとしますと、かれら異教徒は、わたしをナーランダーの街に連れまわして『かの百万長者の資産家ウパーリが、かれの前の信心を捨てて、われらの弟子になったぞ』と、ふれまわるでしょう。ところが、まったくその反対に、世尊はわたしに、もっと調べてみなさい、と助言してくださったのです。世尊の発言に、わたしはいっそう喜びを覚えます。それゆえ、わたしは再び、世尊と真理(ダンマ)と僧団(サンガ)(三宝)に帰依いたします。世尊がわたしを生涯帰依する在家の信者として、お認めくださいますように」

しかしながら、世尊はかれに、さらに、こう助言した。

「資産家よ、長いあいだ、そなたの家はニガンタたちを支援してきました。そなたはわたしの信者になったのであるが、そなたは寛大さと思いやりを実践しなければなりません。そなたは、前の異教の師たちへ托鉢食を布施しつづけるべきです。かれらはいまだに、そなたの支援にたいへん依存しているのですから。そなたはかれらをただ無視して、そなたが布施しつづけていた支援から手を引くことはできないのです」

ウパーリは世尊の助言に、さらに満足し、喜びを覚えて、こういった。

「尊師よ、わたしはゴータマ沙門が、このようにいった、と誤ってきいておりました。

『布施は、わたしにのみすべきである。布施は、わたし以外の者にすべきではない。布施は、わたしの弟子たちにのみすべきである。布施は、わたしの弟子たち以外の者にすべきではない。わたしになされる布施のみに果報があり、他の者への布施にはない。わたしの弟子たちになされる布施のみに果報があり、他の者の弟子たちへの布施にはない』

ところが、まったくその反対に、世尊はわたしに、前の異教の師たちへの布施をうながされました。いずれにせよ、わたしたちはその果報の時を知ることになりましょう、尊師よ。それゆえ、わたしは三たび、世尊と真理(ダンマ)と僧団(サンガ)(三宝)に帰依いたします。世尊がわたしを生涯帰依する在家の信者として、お認めくださいますように」

そこで、世尊は資産家ウパーリに、順次、次第説法された。すなわち、布施論、戒律論、天界の幸福な運命論である。世尊は、感覚的喜びの危険と堕落、汚染について説明され、そして離欲の恩恵についても説明された。(訳注:次第説法は簡潔に、施論、戒論、生天論、愛欲不利益論、離欲利益論の五つとしてまとめられることが多い)資産家ウパーリの心が、従順になり、柔和になり、障碍から解放され、向上心ができて、確信をもっている、と世尊が知られたとき、諸仏に到る特別の教えである四聖諦を説き示された。

ちょうど、すべての染みがとり除かれた清潔な布が、染料で均等に色づけできるように、資産家ウパーリがそこに坐っていたあいだに、法(ダンマ)話の終わりには、かれのなかに遠塵離垢の法の眼が生じたのである。

「生じる性質のものは、すべて、滅する性質のものである」

そのとき、資産家ウパーリは真理(ダンマ)に到達し、真理(ダンマ)を現証した。かれは疑いを渡り、預流者(ソーターパンナ)となった。

かくして、仏教は自由な探究と完全に寛大な精神にひたされているのである。開かれた心と、慈悲の情の教えであり、全宇宙を照らし、温め、智慧と慈悲の二筋の光をともない、穏やかな輝きを、生と死の海でもがいている生きとし生けるものにふりそそいでいる。

※ 画像やテキストの無断使用はご遠慮ください。/ All rights reserved.

Episode 61 ATTITUDE TOWARDS OTHER RELIGIOUS TEACHERS

In the chronicle of the Buddha, there are two personages under the same name of “Upāli”. The first personage is Upāli the barber, whotogether with the six Sākyan princesobtained the higher ordination under the Blessed One at the Anupiya Mango Grove. He was well-versed in the Disciplinary Rules (Vinayadhara) and was appointed as the answerer (vissajjaka) of the Vinaya during the First Buddhist Council.

The second is a millionaire of Bālaka, one of the prominent disciples of Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta. He was distinguished as Upāli-gahapati (Upāli the householder). After hearing the Blessed One’s exposition of the Dhamma, he was so pleased that he instantly expressed his desire to become a follower of the Blessed One. Here is his story:

Once, when Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta was seated together with a very large assembly of laymen from Bālaka led by Upāli, there came Nigaṇṭha Dīgha Tapassī to him. Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta asked: “Where did you come from in this middle of the day, Tapassī?”

“I came from the presence of the ascetic Gotama, Venerable sir.”

“Did you have some conversation with the ascetic Gotama, Tapassī?”

“Yes, I had some conversation with the ascetic Gotama, Venerable sir.”

“What was your conversation with Him like, Tapassī?”

Then, Nigaṇṭha Dīgha Tapassī related to Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta his entire

conversation with the Blessed One:

“This morning, after wandering for alms in Nāḷandā and partaking of

my meal, I went to Pāvārika’s mango grove to see the ascetic Gotama. I exchanged greetings with Him. After this courteous and amiable exchange, He asked me to take a seat; then He asked: ‘Tapassī, how many kinds of action does Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta describe for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action?’”

“Friend Gotama, Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta is not accustomed to use the description ‘action, action (kamma)’; Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta is accustomed to use the description ‘rod, rod (daṇḍa)’.”

“Then, Tapassī, how many kinds of rods does Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta describe for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action?”

“Friend Gotama, Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta describes three kinds of rods for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action; that is, the bodily rod (kāyadaṇḍaṁ), the verbal rod (vacīdaṇḍaṁ), and the mental rod (manodaṇḍaṁ).”

“Of these three kinds of rods, Tapassī, thus analysed and distinguished, which kind of rods does Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta describe as the most reprehensible for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action: the bodily rod, the verbal rod or the mental rod?”

“Of these three kinds of rod, friend Gotama, thus analysed and distinguished, Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta describes the bodily rod (kāyadaṇḍaṁ) as the most reprehensible for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action, and not so much the verbal rod or the mental rod.”

“Do you say the bodily rod, Tapassī?”

“I say the bodily rod, friend Gotama.”

“Do you say the bodily rod, Tapassī?”

“I say the bodily rod, friend Gotama.”

“Do you say the bodily rod, Tapassī?”

“I say the bodily rod, friend Gotama.”

“Thus, Venerable sir, the ascetic Gotama asked me, and I maintained my statement up to the third time. Then, I asked Him: ‘And you, friend Gotama, how many kinds of rods do You describe for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action?’”

“Tapassī, the Tathāgata is not accustomed to use the description ‘rod, rod (daṇḍa)’; the Tathāgata is accustomed to use the description ‘action, action (kamma)’.”

“But, friend Gotama, how many kinds of actions do You describe for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action?”

“Tapassī, I describe three kinds of actions for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action; that is, the bodily action (kāyakammaṁ), the verbal action (vacīkammaṁ), and the mental action (manokammaṁ).”

“Of these three kinds of action, friend Gotama, thus analysed and distinguished, which kind of actions do You describe as the most reprehensible for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action: the bodily action, the verbal action or the mental action?”

“Of these three kinds of actions, Tapassī, thus analysed and distinguished, I describe mental action (manokammaṁ) as the most reprehensible for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action, and not so much the bodily action and the verbal action.”

“Do You say mental action, friend Gotama?”

“I say mental action, Tapassī.”

“Do You say mental action, friend Gotama?”

“I say mental action, Tapassī.”

“Do You say mental action, friend Gotama?”

“I say mental action, Tapassī.”

“Thus, Venerable sir, I made the ascetic Gotama maintain His statement up to the third time, after which I rose from my seat and come here, Venerable sir.”

When this was said, Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta praised him: “Good, good, Tapassī! Nigaṇṭha Dīgha Tapassī has answered the ascetic Gotama like a well-taught disciple who understands his teacher’s dispensation rightly. What does the trivial mental rod count for in comparison with the gross bodily rod? On the contrary, the bodily rod is the most reprehensible for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action, and not so much the verbal rod and the mental rod.”

At that time, Upāli, who was seated in the assembly, was paying close attention to the account narrated by Nigaṇṭha Dīgha Tapassī. He also praised Nigaṇṭha Dīgha Tapassī before Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta and said to him: “Now, Venerable sir, I shall go and refute the ascetic Gotama’s doctrine on the basis of this statement. If the ascetic Gotama maintains before me what the Venerable Dīgha Tapassī made Him maintain, then just as a strong man might seize a long-haired ram by the hair and drag him to, drag him fro, and drag him round about, even so in the debate I will drag the ascetic Gotama to, drag Him fro, and drag Him round about. Venerable sir, I shall go and refute the ascetic Gotama’s doctrine on the basis of this statement.”

Then, Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta urged him: “Go, householder, and refute the ascetic Gotama’s doctrine on the basis of this statement. For either I, Nigaṇṭha Dīgha Tapassī, or you yourself should refute the ascetic Gotama’s doctrine.”

“Yes, Venerable sir,” the householder Upāli replied. Thereafter, he rose from his seat. After paying homage to Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta, keeping him on his right, he left to go to the Blessed One.

Now, on that occasion, the Blessed One was residing in Pāvārika’s mango grove at Nāḷandā, when Upāli the follower of Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta came to Him with the intention to debate Him on volitional actions (kamma). After paying homage to the Blessed One, he sat down at one side and asked: “Venerable sir, did Nigaṇṭha Dīgha Tapassī come here?”

“Nigaṇṭha Dīgha Tapassī did come here, householder.”

“Venerable sir, did You have some conversation with him?”

“I did have some conversation with him, householder.”

“What was Your conversation with him like, Venerable sir?”

Then, the Blessed One related to the householder Upāli His entire conversation with Nigaṇṭha Dīgha Tapassī.

When this was said, the householder Upāli said to the Blessed One: “Good, good, Venerable sir, on the part of Tapassī! Nigaṇṭha Dīgha Tapassī has answered the Blessed One like a well-taught disciple who understands his teacher’s dispensation rightly. What does the trivial mental rod count for in comparison with the gross bodily rod? On the contrary, the bodily rod is the most reprehensible for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action, and not so much

the verbal rod and the mental rod.”

“Householder, if you will debate on the basis of truth, we might have some conversation about this.”

“I will debate on the basis of truth, Venerable sir, so let us have some conversation about this.”

“What do you think, householder? Here, some Nigaṇṭha might be afflicted, is suffering, and is gravely ill with an illness needing treatment by cold water, which his vows prohibit. He might refuse cold water though mentally longing for it, and he might use only the permissible hot water, thus keeping his vows bodily and verbally.

Because he does not get cold water, he might die. Now, householder, where would Nigaṇṭha Nātaputtta describe his rebirth as taking place?”

“Venerable sir, there are gods called ‘mind-bound’ (manosattā devā); he would be reborn there. Why is that? Because when he dies, he is still bound by attachment in the mind.”

“Householder, householder, pay attention to how you reply! What you said before does not agree with what you said afterwards, nor does what you said afterwards agree with what you said before. Yet, you made this statement: ‘I will debate on the basis of truth, Venerable sir, so let us have some conversation about this.’”

“Venerable sir, although the Blessed One has spoken thus, yet the bodily rod is the most reprehensible for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action, and not so much the verbal rod and the mental rod.”

“What do you think, householder? Here, some Nigaṇṭha might be disciplined in four kinds of self-restraint—he is restrained with regard to all water; he is endowed with the avoidance of all evil; he is cleansed by the avoidance of all evil, and he is suffused with the avoidance of all evil—and yet, when going forward and returning, he brings about destruction of many small living beings. What result does Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta describe for himself?”

“Venerable sir, Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta does not describe what is unintentional as greatly reprehensible.”

“But, if one does it intentionally, householder?”

“Then, it is greatly reprehensible, Venerable sir.”

“But, under which of the three rods does Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta describe

intention (cetanā), householder?”

“Under the mental rod, Venerable sir.”

“Householder, householder, pay attention to how you reply! What you said before does not agree with what you said afterwards, nor does what you said afterwards agree with what you said before. Yet, you made this statement: ‘I will debate on the basis of truth, Venerable sir, so let us have some conversation about this.’”

“Venerable sir, although the Blessed One has spoken thus, yet the bodily rod is the most reprehensible for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action, and not so much the verbal rod and the mental rod.”

“What do you think, householder? Is this town of Nāḷandā successful and prosperous? Is it populous and crowded with people?”

“Yes, Venerable sir, it is.”

“What do you think, householder? Suppose a man came here brandishing a sword and spoke thus: ‘In one moment, in one instant, I shall make all living beings in Nāḷandā into one mass of flesh, into one heap of flesh.’ What do you think, householder, would that man be able to do that?”

“Venerable sir, ten, twenty, thirty, forty, or even fifty men would not be able to make all the living beings in Nāḷandā into one mass of flesh, into one heap of flesh in one moment or instant. So what does a single trivial man count for?”

“What do you think, householder? Suppose some ascetic or brahmin who possesses supernormal powers and has attained mastery of mind came here and spoke thus: ‘I will reduce this town of Nāḷandā to ashes with one mental act of hate.’ What do you think, householder, would such a ascetic or brahmin be able to do that?”

“Venerable sir, such an ascetic or brahmin who possesses supernormal powers and has attained mastery of mind would be able to reduce ten, twenty, thirty, forty, or even fifty citizens of Nāḷandā to ashes with one mental act of hate, so what does a single trivial citizen of Nāḷandā count for?”

“Householder, householder, pay attention to how you reply! What you said before does not agree with what you said afterwards, nor does what you said afterwards agree with what you said before. Yet, you made this statement: ‘I will debate on the basis of truth, Venerable sir, so let us have some conversation about this.’”

“Venerable sir, although the Blessed One has spoken thus, yet the bodily rod is the most reprehensible for the performance of evil action, for the perpetration of evil action, and not so much the verbal rod and the mental rod.”

“What do you think, householder? Have you heard how the Daṇḍaka, Kāliṅga, Mejjha, and Mātaṅga Forests became forests?”

“Yes, Venerable sir.”

“As you heard it, how did they become forests?”

“Venerable sir, I heard that they became forests by means of a mental act of hate on the part of the seers.”

“Householder, householder, pay attention to how you reply! What you said before does not agree with what you said afterwards, nor does what you said afterwards agree with what you said before. Yet, you made this statement: ‘I will debate on the basis of truth, Venerable sir, so let us have some conversation about this.’”

“Venerable sir, I was satisfied and pleased by the Blessed One’s very first simile. Nevertheless, I thought I would oppose the Blessed One thus since I desired to hear the Blessed One’s varied solutions to the problem. Magnificent, Venerable sir! Magnificent, Venerable sir! The Blessed One has made the Dhamma clear in many ways, as though He were turning upright what had been overthrown, revealing what was hidden, showing the way to one who was lost, or holding up a lamp in the dark

for those with eyesight to see forms. Venerable sir, I go to the Blessed One for refuge and to the Dhamma and to the Saṁgha. Let the Blessed One remember me as a lay follower who has gone to Him for refuge for life.”

“Investigate thoroughly, householder! It is good for such a distinguished person like you to make first a thorough investigation.”

Upāli was overjoyed at this unexpected remark of the Blessed One. He said: “Venerable sir, had I been a disciple of other sectarians, they would have taken me round the streets of the City of Nāḷandā proclaiming: ‘The millionaire householder Upāli had renounced his former faith and has come to discipleship under us.’ But, on the contrary, the Blessed One advises me to investigate further. The more pleased am I with this remark of Yours. So, for the second time, Venerable sir, I go to the Blessed One for refuge and to the Dhamma and to the Saṁgha. Let the Blessed One remember me as a lay follower who has gone to Him for refuge for life.”

However, the Blessed One advised him further: “Householder, for a long time, your family has supported the Nigaṇṭhas. Although you have become My follower, you should practise tolerance and compassion. You should continue to give alms to your former religious teachers as they still depend very much on your support. You cannot just ignore them and withdraw the support you used to give them.”

Upāli became more satisfied and pleased with the Blessed One’s advice and said: “Venerable sir, I have heard wrongly that the ascetic Gotama says thus: ‘Offerings should be given only to Me; offerings should not be given to others. Offerings should be given only to My disciples; offerings should not be given to others’ disciples. Only what is given to Me is very fruitful, not what is given to others. Only what is given to My disciples is very fruitful, not what is given to others’ disciples.’ But, on the contrary, the Blessed One encourages me to give offerings to my former teachers. Anyway, we shall know the time for that, Venerable sir. So for the third time, Venerable sir, I go to the Blessed One for refuge and to the Dhamma and to the Saṁgha. Let the Blessed One remember me as a lay follower who has gone to Him for

refuge for life.”

Then, the Blessed One gave the householder Upāli a progressive instruction, that is, talk on generosity, talk on virtue, talk on happy destiny of celestial abodes; He explained the danger, degradation and defilement in sensual pleasures, and the blessing of renunciation. When He knew that the householder Upāli’s mind was

ready, receptive, free from hindrances, elated and confident, He expounded to him the Teachings special to the Buddhas—the Four Noble Truths.

Just as a clean piece of cloth with all marks removed would be able to take dye evenly, even so at the end of the Dhamma talk, while the householder Upāli was sitting there, the spotless immaculate vision of the Dhamma arose in him: “All that is subject to arising is subject to cessation.” Then, the householder Upāli attained the Dhamma, realised the Dhamma; he crossed beyond doubt and became a Sotāpanna.

Thus, Buddhism is saturated with this spirit of free enquiry and complete tolerance. It is a teaching of the open mind and the sympathetic heart which, lighting and warming the whole universe with its twin rays of wisdom and compassion, sheds its genial glow on every being struggling in the ocean of birth and death.

※ 画像やテキスト の無断使用はご遠慮ください。/ All rights reserved.

アシン・クサラダンマ長老

1966年11月21日、インドネシア中部のジャワ州テマングン生まれ。中国系インドネシア人。テマングンは近くに3000メートル級の山々が聳え、山々に囲まれた小さな町。世界遺産のボロブドゥール寺院やディエン高原など観光地にも2,3時間で行ける比較的涼しい土地という。インドネシア・バンドゥンのパラヤンガン大学経済学部(経営学専攻)卒業後、首都ジャカルタのプラセトエイヤ・モレヤ経済ビジネス・スクールで財政学を修め、修士号を取得して卒業後、2年弱、民間企業勤務。1998年インドネシア・テーラワーダ(上座)仏教サンガで沙弥出家し、見習い僧に。詳しく見る

奥田 昭則

1949年徳島県生まれ。日本テーラワーダ仏教協会会員。東京大学仏文科卒。毎日新聞記者として奈良、広島、神戸の各支局、大阪本社の社会部、学芸部、神戸支局編集委員などを経て大阪本社編集局編集委員。1982年の1年間米国の地方紙で研修遊学。2017年ミャンマーに渡り、比丘出家。詳しく見る

※ 画像やテキストの無断使用はご遠慮ください。

All rights reserved.