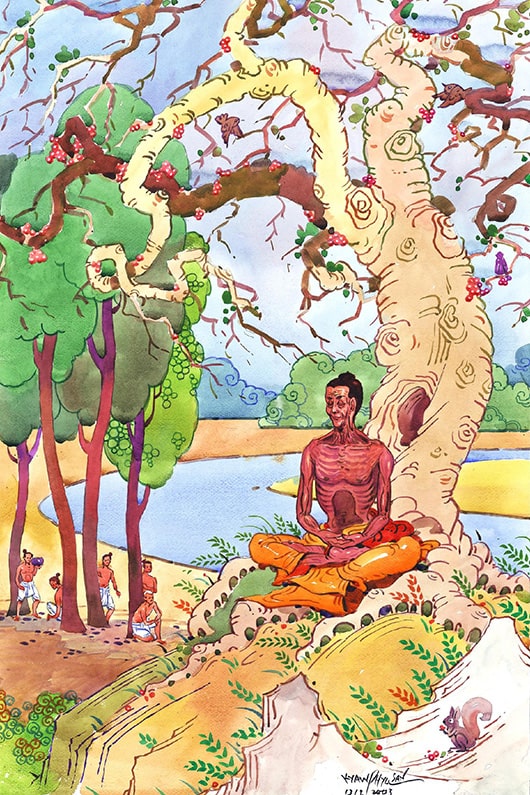

18話 苦行・・・骨と皮に

第2部 成道へ

第1章 苦行

18話 苦行・・・・骨と皮に

菩薩(ボーディサッタ)は明智を探しもとめる旅をつづけた。マガダ国を遍歴し、ついにウルヴェーラーの森に近い市場町セーナーニに着いた。森を念入りに調べ、まわりが静かで穏やかで、うっとりするほど美しい、魅力ある場所をみつけた。森のなかにはきれいに澄みきった清流のネーランジャーラ川が流れている。気持ちのよい平らな砂岸があり、泥や沼はない。森の近くに村があり、森に住んでいる行者たちは托鉢で容易に食べ物が得られるのだ。こうした特色を見て、かれはこう考えた。(善家の子息が涅槃をめざして懸命に取りくむにはまさにぴったりの場所だ)と。したがって、このウルヴェーラーの森に落ちつこうと決めたのである。ここが、かれの精神的な目標を完成させるために、六年もの長きにわたって厳格な修行を実践する場となった。

おそろしく、こわい感情に遭遇する

菩薩はウルヴェーラーの森にいて、こう考えた。

「まさしく遠くはなれた密林の繁みに住むことを耐え忍ぶのはむずかしい。完全に遠離をまっとうするのは、むずかしい。孤立して住むのを楽しむのもむずかしい。なぜなら、心の統一集中がない者には、密林が心を奪うにちがいないからだ」

「仮に、ある行者かバラモンが、こころ、ことば、からだの活動が清らかでないか、邪悪な暮らしをしていて、肉欲、敵意、害意の思考をもち、放逸で、よく気づくことがなく、こころが統一集中せず、混乱し、正知を欠いている、としてみよう。そんな行者かバラモンが、森のなかの遠くはなれた密林の繁みを住まいにするときは、そうした欠点によって、気味悪いおそろしさやこわさを呼びだしてしまうのだ」

「しかし、わたしは、そうした欠点があるものの一人として、森のなかの遠くはなれた密林の繁みを住まいにするのではない。わたしは、そんな欠点がない気高く貴いものの一人として、森のなかの遠くはなれた密林の繁みを住まいにするのだ。そうした欠点から自由なわたし自身の内部を見ていて、森に住むのは大きな慰めだ、とわかる」

そこにいるあいだ、菩薩もまた、おそろしさやこわさの感情に遭遇した。

「満月とか新月とか、そして月の八日目の四半分の弦月の特別な聖夜、わたしはかつてそんな夜を、もっとも厄介な、恐怖でぞっとする果樹園で、密林の繁みで、大樹の下で、こわい光景や出来事、夢を見ながら、髪が極限まで逆立つような思いをして過ごした。そこにいたときには、鹿が近寄ってきたり、孔雀が枝をバサッとはたいたり、風が葉末を揺すってカサコソさせたりした。そんなときわたしは考えたのである。『確かにこれは、おそろしさやこわさがやってきているのだ』と」

「そんな瞬間に、わたしは薄気味悪く感じたのだが、こんな思いも心に浮かんだ。『なぜわたしは、おそろしさやこわさを、つねに待ち受けているのだろうか? おそろしさやこわさを、いまわたしがとっている姿勢を持続することで、静めてみてはどうであろうか?』」

「それから、歩いているあいだにおそろしくなったときはいつでも、わたしは、立つことでも坐ることでも横になることでもなく、歩くことを持続することによっておそろしさやこわさを静めた。立っているあいだにおそろしくなったときはいつでも、わたしは、歩くことでも坐ることでも横になることでもなく、立つことを持続することによって、おそろしさやこわさを静めた。坐っているあいだにおそろしくなったときはいつでも、わたしは、歩くことでも立つことでも横になることでもなく、坐ることを持続することによって、おそろしさやこわさを静めた。横になっているあいだにおそろしくなったときはいつでも、わたしは、歩くことでも立つことでも坐ることでもなく、横になることを持続することによって、おそろしさやこわさを静めた」

五群行者が菩薩に合流する

生後五日の赤ちゃんだった菩薩を、いつかブッダになるだろう、といちばん若いバラモンのコンダンニャが予言してから、およそ二十九年たっていた。コンダンニャはシッダッタ王子の出家の日を待ちつづけていたのである。そしてその間はいつも、王子が世を捨てたかどうか、かれはきいていたのだ。いまやもう、かなり老人になっていたが、自分の予言を確信しており、待ち続けることに希望を失っていなかったものの、将来を予言した八人のバラモンのうち、かれ以外の七人はすでに亡くなっていた。アーサーラー月の満月の日に王子が出家した、と伝え聞いたとき、ついに幸福な日がやってきたのである。亡くなったほかのバラモンの息子たち四人に、ただちに話をもちかけた。ワッパ、バッディヤ、マハーナーマ、アッサジである。かれらに、いっしょに世を捨て菩薩に合流しよう、と説得したのだ。

それからこの五人の行者はいくつかの王国の村や市場町を訪れ、菩薩を探し、ついにウルヴェーラーの森でみつけた。かれらは菩薩に側近として仕えたが、菩薩はもっとも厳しいかたちの苦行に従事して、ほどなくブッダになり、解脱の道を教えてくれるだろうという強い希望をもっていた。ウルヴェーラーの森で六年の間、かれらは菩薩の付き人として、まわりの掃除や、お湯や水をもってくるなどの務めを果たしたのだ。

火起こし~三つのたとえ

ある日、菩薩の心に、三つのたとえが自然発生的に浮かんだ。それは、これまできいたことがないものであった。

「たとえば、ある男が摩擦発火の火起こし棒で、水の中にひたされ、樹液を含んで濡れている木片をこすって火をつけようと思っても、火をつけることはできない。なぜなら木片は濡れていて、水にひたされているからだ。そのかわりにくたびれてへとへとになり、失望するだけだろう。ちょうどそのように、この世に肉体的にも精神的にも官能の欲望や感覚の対象からはなれていない行者やバラモンがいるのだが、かれらは熱心に修行して、苦しく、苛酷で、身を刺すような思いをしているのに、道や果のさとりを得ることはなく、みじめになるだけだろう」

これが第一のたとえで、自然発生的にかれに浮かんだのだが、これまできいたことがなかった。このたとえは《妻子持ち(妻帯)(サプッタバリヤー)出家(パッバッジャー)》と呼ばれる行者の類型を示している。すなわち禁欲主義のかたちをとりながらも、そんな行者やバラモンは、妻やこどもとの在家の生活を、そのまま送っているのだ。

「また、たとえば、ある男が摩擦発火の火起こし棒で、水から遠くはなれた地面の上に置かれ、樹液を含んで濡れている木片をこすって火をつけようと思っても、やはり火をつけることはできない。なぜなら木片が水から遠くはなれた乾いた地面の上に置かれていても樹液を含んで濡れているからだ。そのかわりにくたびれてへとへとになり、失望するだけだろう。ちょうどそのように、この世に肉体的には官能の欲望や感覚の対象からはなれている行者やバラモンがいるのだが、精神的にはそうではないのだ。かれらは熱心に修行して、苦しく、苛酷で、身を刺すような思いをしているのに、道や果のさとりを得ることはなく、みじめになるだけだろう」

これが第二のたとえで、自然発生的にかれに浮かんだのだが、これまできいたことがなかった。このたとえは《バラモン持法者(邪教信者)(ブラーフマナダンミカー)の出家》と呼ばれる行者の類型を示している。すなわち禁欲主義のかたちをとり、在家の生活や妻子を捨てていながらも、そんな行者やバラモンは、誤った実践にみずからを捧げているのだ。

「さらにまた、たとえば、ある男が摩擦発火の火起こし棒で、水から遠くはなれた地面の上に置かれ、樹液がなく乾いた木片をこすって火をつけようと思うと、火をつけることができて容易に熱を生じさせられる。なぜなら木片が水から遠くはなれた乾いた地面の上に置かれていて、樹液を含まず、乾いているからだ。ちょうどそのように、この世に肉体的にも精神的にも両方とも官能の欲望や感覚の対象から完全にはなれている行者やバラモンがいるのだ。かれらは熱心に修行して、苦しく、苛酷で、身を刺すような思いをしていても、いなくても、どちらでも正しい実践をして、道や果のさとりを得るだろう」

これが第三のたとえで、自然発生的にかれに浮かんだのだが、これまできいたことがなかった。このたとえは《菩薩の出家(パッバッジャー)》と呼ばれる行者の類型を示し、菩薩自身が実践しているものだった。

止息禅定の開発実践

ウルヴェーラーの森で菩薩は、もっとも厳しい種類の苦行すべてを実践することで、明智をめざして悪戦苦闘した。苦行とは「なしがたい行為(ドゥッカラチャリヤ)」と呼ばれ、ふつうの人には実践がむずかしいものだ。かれは四重の強い決意をした。それは「精勤精進(パダーナヴィリヤ)」と呼ばれ、次のようなものである。

「わが皮膚のみ残れ! わが筋のみ残れ! わが骨のみ残れ! わが肉と血は干からびよ!」

この決意によって、かれは一瞬たりとも退却せず、実践において、全力をあげて奮闘したのである。

そのとき、次のような考えがかれに浮かんだ。「もしわたしが歯を食いしばり、舌を口蓋に押しつけ、健全な心で不健全な心を制御し、制圧し、破壊したら、それは善いことだろう」と。

かくして、ちょうど強い男が弱い男の頭や肩をつかんで押さえ込むように、かれは歯を食いしばり、舌を口蓋に押しつけ、健全な心で不健全な心を制御し、制圧し、破壊した。かれが悪戦苦闘している間、汗が腋の下からポタポタ滴った。

そのとき力の入れ具合が弱まったのではなく、かれのなかから強い活力が勢いよく生まれてきたのだ。かれの気づきは確立され、混乱はなかった。しかし苦しい努力によって、かれの全身は極度に興奮し、平穏ではなかった。苦しいという感情がかれのなかに生まれはしたが、奮闘をつづける意思はびくともせず、ひるまなかった。

このとき菩薩は、こう考えた。「わたしは無呼吸による止息禅定をこころみてはどうであろうか!」

そこで必死の努力で、口と鼻から、吸うのと吐くのを止めた。出入りの機会がなくなって、息は両耳をとおして抜けたが、特別にうるさい音をたてた。ちょうど鍛冶屋のふいごが特別な轟音をたてるように、かれの両耳から出入りする息が轟音をたてたのである。

また、かれに考えが浮かんだ。「わたしはまた、無呼吸による止息禅定(アッパーナカジャーナ)を、こころみてはどうであろうか!」

そこで必死の努力で、口と鼻と耳から、吸うのと吐くのを止めた。口と鼻と耳からの出入りの機会がなくなって、息の風がかれの頭を打ち、刺し、ひどく苦しめた。ちょうど強い男が鋭くとがった錐で頭を突き通すように、かれの頭を息が強烈な暴力でひどく苦しめた。

さらにまた、かれに考えが浮かんだ。「わたしは、無呼吸による止息禅定(アッパーナカジャーナ)を、こころみつづけてはどうであろうか!」

そこで必死の努力で、前のように、口と鼻と耳から、吸うのと吐くのを止めた。かれがそうしたとき、激しい痛みが頭のなかに生まれた。ちょうど強い男が硬い革ひもをかれの頭に巻いて棒切れでねじってギリギリ締めつけるかのようであった。

それでもまた、かれに考えが浮かんだ。「わたしは、無呼吸による止息禅定(アッパーナカジャーナ)を、それでもこころみつづけてはどうであろうか!」

そこで必死の努力で、前のように、口と鼻と耳から吸うのと吐くのを止めた。その後すぐに、猛烈な息の風がかれのおなかを切り刻んだ。ちょうど手際のよい肉屋かその徒弟がウシの腹肉を鋭利な刃物で切り刻むかのようで、そのように、たっぷりの息がかれのおなかを刺した。

もう一度、かれに考えが浮かんだ。「わたしは、無呼吸による止息禅定(アッパーナカジャーナ)を、それでもこころみつづけてはどうであろうか!」

そこで必死の努力で、前のように、口と鼻と耳から、吸うのと吐くのを止めた。かれがそうしたとき、全身が猛烈に灼けつくような熱病(ダーハローガ)にかかった。ちょうど強い男ふたりが、ひとりの弱い男の両手をつかんで、真っ赤に熾っている石炭の凹みで炙っているかのようだった。

このようにかれが止息禅定をさらにさらに過酷にやるたびに、かれに奮起する力が生まれつづけた。だからかれの気づきは確立され、混乱はなかった。しかしながら苦しい努力によってかれの全身は極度に興奮し、平穏ではなかった。苦しいという感情がかれのなかに生まれはしたが奮闘をつづける意思はびくともせず、ひるまなかった。

かれの全身はあまりに極端な強い熱に打ちのめされ、歩いているうちに卒倒して、崩れ落ちて坐位になった。そのとき、かれがそのように崩れ落ちるのを見た神々は「沙門ゴータマは死んだ」といった。別の神々は「沙門ゴータマは死んではいないが、かれは死につつある」といった。さらにまた別の神々は「沙門ゴータマは死んでいないし、死につつあることもない。沙門ゴータマは阿羅漢であり、尊者であり、そのような道に阿羅漢は持ちこたえてとどまる」と、いったのである。

断食の実践

ほんの少しのあいだ、気が遠くなった後、意識が戻ってきた。そして活力と気づきも戻った。そのときかれは、からだをちょっと新鮮にするため、長く吸って吐く深呼吸を何度かした。そのあと立ち上がり、樹下のかれの坐所に行った。その瞬間、こう考えたのだ。「わたしは完全な断食の実践をしたらどうであろうか!」と。

そのあとすぐに、ある神々がかれに近づいてきて、こういった。

「おお、気高く貴い沙門よ、完全な断食の実践をなさいませんように! 食べ物をまったく食べないのなら、われらは神の食べ物をあなたの毛穴から注入することになりましょう。その食べ物で、あなたは命を持ちこたえるでしょう」

神々がかれにどのようにするのかをきいて、菩薩はこう考えた。「もし、わたしが完全に食べ物を食べないと決めたら、これらの神々はわたしの毛穴から神の食べ物を注入することになろう。わたしはそれによって命を持ちこたえるであろうが、そのときわたしは偽りをいっていることになろう」と。

だからかれは断って「必要ありません」といったのである。

それから、こんな考えがかれに浮かんだ。「もし、わたしが一日の食事を、ほんの少しずつ食べるのなら、それは善いことではなかろうか。たとえば少量のインゲン豆のスープか、少量の穀物のスープか、少量の扁平なレンズ豆のスープか、少量のエンドウ豆のスープを!」

そこでかれがそうしてみると、からだがだんだん痩せてやつれ、極度の羸痩(やせ衰えた)の状態になった。栄養の欠如から、からだと手足の関節が突き出ていた。まるで、茎が節くれだっているニワヤナギか大きな藺草(訳注:アーシーティカやカーラと呼ばれる草か蔓)のようであった。かれの臀部は指が二本のラクダの蹄のようになり、肛門は凹んでしまった。かれの背骨は大きな数珠玉が数珠つなぎに浮き出ているかのようであった。肋骨の間の肉は落ちこんで、肋骨が古い家の垂木のように突き出ていた。両目の眼球は眼窩に落ちこみ、ちょうど深井戸の奥底に映る二つの星のようであった。頭皮はしなびてしおれ、末成り瓢箪が風に吹かれて日に晒されて、しなびてしおれたみたいであった。

もし、かれが自分のおなかにさわると、背骨にまでさわってしまうほどであった。そしてもし、背骨にさわると、おなかにまでさわってしまうほどであった。おなかの皮が栄養物の欠如のせいで背骨にまとわりついていたのである。かれが排泄のためにしゃがむと、キンマの果実である檳榔子(訳注:長さ六~八㌢の卵形)くらいの大きさの固い玉が、せいぜい一、二個、なんとか排出されるのだ。小水もまた、まったく出なかった。小水になるのに足りるほど水分のある食べ物が、おなかになかったのである。からだがあまりに弱っていて、以上のようなことをすると、顔を下にしてばったりその場に崩れ落ちた。もし、かれが自分のからだを落ちつかせるために両手で手足をこすると、肉と血から十分に栄養がまわっていないために、体毛がぽろぽろ毛根からはがれ落ちてしまうのであった。

そんなとき、かれを見た人びとは、このようにいった。「沙門ゴータマの顔は真っ黒だ」別の人びとは「沙門ゴータマの顔は真っ黒ではない。茶色だ」その他の人びとは「沙門ゴータマの顔は真っ黒でも茶色でもない。黄褐色だ」輝くばかりに明るい黄金色であったかれの顔の色は、あまりにも食べ物を食べていないために、ひどく劣化していたのである。

ある日、かれが歩いて行ったり来たりしているとき、またも気が遠くなり、顔を下にして崩れ落ちた。耐えがたい熱に悩まされ、栄養が足りていないせいだった。ウルヴェーラーの森の近くに住んでいる人びとは菩薩がもう何日も、ほとんど何も食べていないことを知っていたのだ。そんなとき、ひとりの羊飼いの少年が、菩薩が倒れた場所にたまたま通りかかった。かれは菩薩があまりに断食をしすぎたので、もう死にかけているのだ、と思ったのだ。かれはすぐさま菩薩に近寄り、起こそうとした。菩薩が意識を取り戻したあと、かれは菩薩の頭をひざの上に乗せ、山羊の乳を飲ませた。菩薩は感謝の思いを伝え、羊飼いの少年が健康で幸福でありますように、と祈ったのである。

「悪魔の十軍」を制圧する

出家から六年後、菩薩は危機的な局面に至った。かれはほとんど死の瀬戸際だった。しかしながら、かれはいまだに最高度の精勤(パダーナ)の意思があった。ネーランジャーラ川に近いウルヴェーラーの森で、止息禅定をくりかえしこころみていたのである。

この情況を読みとって、悪魔(マーラ)のナムチがただちに見せかけの善意とあわれみを装い、かれに近づいて、こういった。

「おお気高く貴い王子よ、あなたはいまやひどく痩せている。あなたのからだはまばゆい光彩を失い、ひどく衰えた。死が間近に来ている。生きながらえる見こみは千に一つだ。生きよ、おお気高く貴い王子よ! 生きるのが、より好ましい道だ。もし長生きすれば、功徳を積める。禁欲行の清らかな生活をして、生け贄供養の護摩の儀式をいとなめる。そうすれば、さらに多大な功徳が得られるであろう。この苦行の実践は何の役に立つのか? この古い径は耐えがたい! あなたの目標は達成しがたい! この実践には確かさがない! まさに、こんな道を歩んでゆくのは実行可能なことではない!」

悪魔の誘惑に答えて、菩薩が大胆に、はっきりこういった。

「おお、悪しき者よ、おまえはいつでも有情を輪廻(サンサーラ)の転生に縛りつけ、いつでも有情の解脱を邪魔している。おまえがここにきたのは、ただ自分の利益のためだけだ」

「わたしは苦の輪廻にみちびく世間の善業を微塵も必要としていないのだ。悪魔よ、そのような世間の善業を切望する者たちだけ、おまえは誘惑すればよいのだ」

「わたしの確信(サッダー)は堅固で、まもなく確実に涅槃をさとるであろう。わたしには精進(ヴィリャ)があふれんばかりで、草ぼうぼうの汚らしいがらくたは燃やして灰にできる。わたしの智慧(パンニャー)はくらべるものがなく、岩山の如き無明(アヴィッジャー)をこなごなに砕ける。わたしの念(サティ)(気づき)は偉大で、わたしが覚者(ブッダ)になるようにみちびき、無思慮から自由にする。わたしの定(サマーディ)(統一集中)は須弥山(メール)のように揺らがず、嵐にもびくともしない」

「おお、悪魔よ、止息禅定(アッパーナカジャーナ)を開発する激しい修行によって起きたわたしのからだのこの風は、ガンジス、ジャムナー、アチラヴァティー、サラブー、マヒーというインド五大河の流れでも干あがらせることができるのだ。だから、このような苦行中に、わたしの心は涅槃に向けられているのに、体内のわずかな血を、なぜわたしが干あがらせられないことがあろうか?」

「もし、血が干あがったら、胆汁、痰、小便、栄養成分も干あがる。そして肉も、たしかに消耗するだろう。しかし、胆汁、痰、小水、栄養成分がこのようになくなれば、わたしの心は、さらにきれいになる。念も慧も定もさらに育ち、確かなものとなる」

「わたしは極度の苦痛を経験し、わたしの全身はほとんど炎を噴き出さんばかりの程度まで干あがり、それによってわたしは完全に消耗しているが、わたしの心は絶対に官能の肉欲によっては横道に逸れていない。おお、悪魔よ、おまえが見ているものは、最善の性質を満たしている比類なき人間の心の清浄と高潔さである」

「おまえの第一軍は〈愛欲(カーマ)〉だ。第二軍は禁欲行の清らかな生活への〈反感(アラティ)〉で、第三軍は〈飢えと渇き(クッピーパーサー)〉だ。第四軍は〈渇愛(タンハー)〉、第五軍は〈無気力(ティーナ)と眠気(ミッダ)〉、〈恐怖(ビール)〉が第六軍、〈疑う(ヴィチキッチャー)こと〉が第七軍である。第八軍は〈偽善(マッカ)と強情(タンバ)〉で、第九軍は不正な〈利得(ラーバ)、名声(シローカ)、尊敬(サッカーラ)〉、第十軍は〈自画自賛(アットゥッカンサナ)と他者毀損(パラヴァンバナ)〉である」

「悪魔のナムチよ、これがおまえの十軍だ。その威力で、人間、神々、バラモンが苦の輪廻から解脱することを邪魔しているのだ。偉大な確信、意欲、精進、智慧をそなえた勇者以外、悪魔の十軍を征圧できる者はいない。その勝利が、道と果のさとりと涅槃をもたらすのである」

この当時の戦士は決死の覚悟を示す誓いのしるしとしてムンジャ草の葉を身につけて戦いに挑んだ、といわれているが「降参して退却しないしるしとして、わたしはムンジャ草を身につけている。もし、わたしが戦いから退却せざるをえなくなり、おまえに敗北してこの世に生きながらえたら、それは不名誉で、ぶちこわしで、みっともないことであろう。おまえの軍勢に打ち負かされて敗北を認めるくらいなら、むしろ戦場で死んだほうがはるかにましだ」

「この世には煩悩(キレーサ)の戦場に行く行者やバラモンがいるが、抵抗力はなく、おまえの十軍に制圧されている。かれらはまるで灯りなしに闇に入ってしまった者のようだ。道理にかなった正道を知らず、そこを歩みもしないのだ」

「おお、悪魔よ、おまえの軍勢を四方八方すべてに配置しても、わたしは微塵もこわくない。さあここで、わたしはおまえと戦おう。おまえは、わたしがいまいる場所からわたしを追い払うことはできない。おまえの軍勢に、世間はそのすべての神々とともに勝てないが、わたしはいま、わたしの智慧で、悪魔の十軍を滅ぼすであろう。ちょうど石一つで、火がとおっていないナマの土の鉢をこなごなに砕くように」

菩薩が発したこんな勇ましいことばをきいて、悪魔はひとことも答えられずに、その場を去ったのであった。

明智への別の道を熟考する

ある日の午後、前日に気が遠くなったあと菩薩は羊飼いの少年が飲ませてくれた山羊の乳のおかげで生気を取り戻し、気分がよくなったことを思い返していた。あれがなければ死んでいたかも知れない。

そう考えていたとき、街へ向かう少女の一団が近くを横切った。歩きながら、このように歌っている。

・・・もし、わたしたちが弦をゆるめすぎれば、竪琴の音は出ないでしょう。

もし、わたしたちが弦をきつく締めすぎれば、竪琴はバラバラにこわれるでしょう。

もし、弦を弱すぎず強すぎず締めれば、竪琴は甘い調べを奏でるでしょう・・・。

少女たちの歌う歌詞が、かれの気持ちを深く動かした。まだ宮殿で暮らしていたときは、あまりにもあらゆる感覚の楽しみにふけっていた。ちょうど竪琴の弦のゆるめすぎのように、みずからの気ままな放埒をとおしてだと、明智はさとれないのである。ちょうど竪琴の弦のきつく締めすぎのように、みずから死の淵の手前までいく苦行をとおしてだと、明智はさとれないのである。

紀元前588年、ウェーサーカー月(訳注:現代暦の5月ごろ)の新月から満月へ月が満ちていく最初の日、菩薩に、こんな考えが浮かんだ。(過去の行者やバラモンは苦行の実践では、しょせんこの程度が最大限である痛みとつらさを体験することができたにすぎない。かれらは、わたしがいま耐えているつらさ以上には体験できなかったのだ。だから未来の行者やバラモンも同じで、現在のかれらも同じである。しかし、みずから死の淵の手前までいく苦行のこの激しい実践では、気高く貴い者の智慧と洞察にふさわしい、人間の置かれた条件より高度な超越の道へ、わたしは達することができなかった。明智への別の道があるのではないだろうか?)

そのとき、かれはこども時代のめでたい祭り「国王犂耕祭」のことを思い出した。父王スッドーダナは幼い王子を連れていき、蒲桃の木の涼しい木陰に王子を置いて、子守りたちに面倒をみさせたのだ。かれは官能の欲望からも、不健全なことからも、まったくはなれていた。そのときかれは冥想をはじめ、出息・入息(アーナパーナ)の修習(バーワナー)をして、遠離から生まれた幸福と喜びとともに、考えつつ、探求しつつ、色界(ルーパワチャラ)の第一禅定(ジャーナ)に達したのだった。このことを思い出したすぐその後で、かれは「ああ、あれが明智への道だ」と、わかったのである。

かれはさらに、よく考えた。「なぜ、わたしは、そのような喜びを恐れるべきであろうか? 純粋に出離(ネッカンマ)から生じた至福で、官能の欲望からまったく離れているのだ。わたしは確かに出息・入息(アーナパーナ)修習(バーワナー)の禅定の至福を恐れてはいない」

そのときまた、かれはさらに考えつづけた。「からだがこれほど衰弱していては出息・入息(アーナパーナ)の修習(バーワナー)をして禅定の至福の達成をするのは不可能だ。この実践を真剣にやる前に何か身のある食べ物か粗食でも、たとえば炊いたご飯とパンを食べて、衰弱したからだに活力を取り戻したほうがよさそうだ」

このように考えて、それからは菩薩は市場町セーナーニへ托鉢に行き、毎朝、食事した。そのようにすることによって衰え弱ったからだを維持した。二、三日後には体力を回復し、大人相(マハープリサ)の特徴も回復した。それは苦行(ドゥッカラチャリヤ)の実践以来、消えていたものだったが、また、はっきりと現れたのである。

五群行者が菩薩から去る

菩薩の側近として仕えていた五行者は、六年間、大きな希望をもって(どんな真理であれ、菩薩がさとられたことはわれらに分かち教えてくださるだろう)と、考えていた。しかしいまや、菩薩がどんな粗食であれ提供されたものは食べるというやりかたに変えたのを見てがっかりし「菩薩は放埒になってしまわれた。闘いを放棄して、贅沢に戻られた」と、不平不満をこぼしたのである。

したがって、五行者はかれのもとを去り、バーラーナシー近くの仙人集会所(イシパタナ)にある鹿野苑(鹿の園(ミガダーヤ))へ行った。側近の付き人だった五行者に見捨てられ、菩薩はウルヴェーラーの森に、ひとりで住んだ。五行者の存在は明智への偉大な闘いで助けにはなったのだが、ひとりになったいま、かれは気落ちしていなかったどころか、このほうが好都合であった。かれはひときわ目につく孤独を得た。その孤独は、尋常ならざる進歩の達成にみちびいてゆく力があり、精神統一を強めるものであった。

菩薩が苦行をしていたのは数日数か月ではなく、六年もの長いあいだ、連続してやっていたのである。あまりに厳しく徹底した実践であったために、栄養の欠如で、かれの筋肉や腱はしなびて縮み、血は干あがり、両目は落ちこんだ。体内から発する熱で黄金色の皮膚は黒ずんだ。かくして骨と皮しか見えなくなっていた。生ける骸骨であった。苦行の実践において他のどんな行者も凌駕することはできなかった。そして、そうしたすべての困難と苦痛を体験したにもかかわらず、かれは決してそれを嘆き悲しむことがなかった。それどころか特異だったのはかれの顔で、痩せこけているのにつねにほほえみを浮かべ、まるでどんな苦痛にも悩まされていないかのようであった。

そのつらいときのあいだ、かれの心に、次のような考えは決して浮かばなかった。「この長きにわたって、すべてのわたしの体力と能力を使ってきた。そしてこの長きにわたってすべて耐え、最も過酷な痛みにも耐えた。しかし、一切智を達成していないのだ! まさに、わたしがやったことは役に立たない! わが宮殿に帰ろう! カピラヴァットゥの王座はわたしのもので、唯一の王位継承者だ。そしてわたしは大人相(マハープリサ)の特徴をもっているので転輪聖王に確実になるであろう。宮殿で、わたしは美しい妃ヤソーダラーと、まだ生きている母、父、八万人の親族と幸福に暮らすであろう。神のようにすべての贅沢を楽しむことができる。なぜ、わたしはこの森で時を無駄にしなければならないのか?」

かれのなかには安易にみずから気ままで放埒な生活をもとめる考えなどは、これっぽっちもなかったのである。

※ 画像やテキストの無断使用はご遠慮ください。/ All rights reserved.

Episode 18. THE PRACTICE OF SEVERE AUSTERITIES

The Bodhisatta continued his quest for Enlightenment. He wandered round the Magadha Country; finally he arrived at the market town of Senāni, with the Uruvelā Forest nearby. When he inspected the forest, he found it to be a lovely and charming spot where the surroundings were quiet and peaceful. Within the forest, flowed the Nerañjarā River with its clean and clear currents; it had a pleasant and smooth sandy

bank, free of mud and mire. Near the forest, there was a village where forest dwelling ascetics could obtain alms-food easily. Having seen all these features, he thought: “Suitable indeed is this place for sons of good families to struggle for Nibbāna.” Accordingly, he resolved to settle down in the Uruvelā Forest, where for six long

years he engaged in an austere practice of ascetism to achieve his spiritual goal.

Encountering the Fearful and Dreadful Feelings

When the Bodhisatta stayed in the Uruvelā Forest, he thought:

“Indeed, it is hard to endure dwelling in a remote jungle-thicket; it is hard to achieve complete seclusion; and it is hard to enjoy living in isolation; for one who has no concentration, the jungles must have robbed his mind.”

“Suppose some ascetic or brahmin is not purified in mental, verbal, bodily action or in his livelihood, is malevolent, with thoughts of sensual desires, thoughts of ill-will, and thoughts of cruelty, is forgetful and not fully aware, unconcentrated and confused in mind, devoid of understanding—when some such an ascetic or brahmin resorts to a remote jungle-thicket abode in the forest, owing to those faults

he evokes unwholesome fear and dread.”

“But I do not resort to a remote jungle-thicket abode in the forest as one of those who are not free from those defects. I resort to a remote jungle-thicket abode in the forest as one of the noble ones who are free from these defects. Seeing in myself this freedom from such defects, I find great solace in living in the forest.”

During his stay there, the Bodhisatta also encountered such feelings as fear and dread: “On the special holy nights of the full-moon or new-moon days, and on the quarter-moon of the eighth, once I spent those nights in the most difficult and frightening orchards, in the jungle-thickets, and under a big tree, witnessing dreadful scenery, incidents and dreams, which made my hair stood on end. And when I dwelt there, a deer would approach me, or a peacock would knock off a branch, or the wind would rustle the leaves. Then I thought: ‘Certainly this is the fear and dread coming’.”

“At such moments, I felt eerie, but then a thought came up in my mind: ‘Why do I dwell in constant expectation of fear and dread? What if I subdue that fear and dread by keeping the posture I am in?’”

“Then, whenever I became frightened while walking, I subdued that fear and dread by keeping on walking, and not by standing, sitting, or lying down. Whenever I became frightened while standing, I subdued that fear and dread by keeping on standing, and not by walking, sitting, or lying down. Whenever I became frightened while sitting, I subdued that fear and dread by keeping on sitting, and not by walking,

standing, or lying down. Whenever I became frightened while lying, I subdued that fear and dread by keeping on lying, and not by walking, standing, or sitting.”

The Group of Five Ascetics (Pañcavaggiyā) Joined the Bodhisatta

It had been about twenty-nine years that Koṇḍañña—the youngest brahmin who foretold that the five-day-old baby Bodhisatta would someday become a Buddha—had been waiting for the day of renunciation of Prince Siddhattha. During that period, he always enquired whether the prince had renounced the world. He had grown quite old by now, but being convinced of his own prediction he was not discouraged waiting, even though his friends, the seven other brahmins, had passed away. Finally, the happy day came when he heard that the prince had gone forth on the full-moon day of Āsāḷha. He immediately approached the four sons of the other brahmins: Vappa, Bhaddiya, Mahānāma and Assaji. He persuaded them to renounce the world together and join the Bodhisatta.

Then, this group of five ascetics began to visit villages and market towns of several kingdoms to look for the Bodhisatta. They finally found him in the Uruvelā Forest. They waited upon him with strong hopes that in no long time, the Bodhisatta, who was engaged in the most severe form of austerities (dukkaracariya), would become a Buddha and would teach them the way to deliverance. While accompanying the Bodhisatta for six years in the Uruvelā Forest, they fulfilled their duties such as sweeping the surrounding place, fetching him hot and cold water, and so on.

The Three Similes of Fire-Making

One day, there arose spontaneously in the Bodhisatta’s mind three similes never heard before. “Just as a man who wants to make fire rubs a fire-kindling stick with

a wet, sappy piece of firewood lying in water, he cannot light a fire because of the wetness of the firewood and because it is lying in water; instead he will only reap weariness and disappointment. Even so, in this world there are ascetics and brahmins who are not detached from sensual desires and from sense-objects, both physically and mentally; although they feel painful, racking, and piercing feelings due to their striving, they will not realise the Path and Fruition, but will only become miserable.” This was the first simile which spontaneously occurred to him, never heard before. This simile signified the type of asceticism called saputtabhariyā-pabbajjā, i.e.

the form of asceticism whereby ascetics and brahmins still lead household lives, with wives and children. “Again, just as a man who wants to make fire rubs a fire-kindling

stick with a wet, sappy piece of firewood lying on land far from water, he still cannot light a fire because of the wetness of the firewood even though it is lying on dry land far from water; instead he will only reap weariness and disappointment. Even so, in this world there are ascetics and brahmins who are physically detached from sensual desires and from sense-objects, but not mentally. Although they feel painful, racking, and piercing feelings due to their striving, they will not realise the Path and Fruition, but will only become miserable.” This was the second simile which spontaneously

occurred to him, never heard before. This simile signified the type of asceticism called brāhmaṇadhammikā-pabbajjā, i.e. the form of asceticism whereby ascetics and brahmins, who have renounced the household lives, their wives and children, devote themselves to the wrong practice. “And again, just as a man who wants to make fire rubs a fire-kindling stick with a dry, sapless piece of firewood lying on land far from

water, he can light a fire and produce heat easily because of the dryness and saplessness of the firewood and because it is lying on dry land far from water. Even so, in this world there are ascetics and brahmins who are completely detached from sensual desires and from sense-objects, both physically and mentally; whether or not they feel painful, racking, and piercing feelings due to their striving, they will in either case realise the Path and Fruition when they follow the correct practice.” This was the third simile which spontaneously occurred to him, never heard before. This simile signified the type of asceticism called Bodhisatta-pabbajjā, practiced by the Bodhisatta himself.

The Practice of Developing the Appāṇaka Jhāna

In the Uruvelā Forest, the Bodhisatta struggled for Enlightenment by practising all of the most severe forms of austerities—called dukkaracariya—which were difficult for ordinary people to practise. He made a strong fourfold determination—called padhāna-viriya—thus: “Let only my skin remain! Let only my sinews remain! Let only my bones remain! Let my flesh and blood dry up!” By this determination, he would not recede even for a second, but would exert the highest effort in the practice.

Then, the following consideration occurred to him: “It would be good if I, with my teeth clenched and my tongue pressed against the palate, were to hold down, subdue and destroy my unwholesome mind with my wholesome mind.”

Thus, just as a strong man might seize a weaker man by the head or shoulders and press him down, even so did he, with his teeth clenched and his tongue pressed against the palate, hold down, subdue and destroy his unwholesome mind with his wholesome mind. While he struggled thus, sweat streamed forth trickling from his armpits.

At that time, instead of slackening in exertion, strenuous effort aroused in him very vigorously. His mindfulness was established and unperturbed. But due to the painful effort, his whole body was overwrought and uncalm. Although such painful feelings arose in Him, his willingness to pursue the struggle remained unflinching.

Then, the Bodhisatta thought thus: “What if I were to develop the appāṇaka jhāna by non-breathing meditation!”

Accordingly, with strenuous effort he stopped inhalation and exhalation through his mouth and nose. Having no chance to come in or to go out, the air escaped through the ears creating an exceedingly loud noise. Just as a blacksmith’s bellows being blown made an exceedingly loud noise, even so was the noise created by the air

coming from his ears.

Again, it occurred to him: “What if I were to develop the appāṇaka jhāna again!”

Accordingly, with strenuous effort he stopped inhalation and exhalation through his mouth, nose and ears. Having no chance to escape through the mouth, the nose, and the ears, the winds racked his head battering and piercing it. Just as if a strong man were to bore one’s head with a sharp and pointed drill, even so did the air rack

his head with great violence.

And again, it occurred to him: “What if I were to go on developing the appāṇaka jhāna!”

Accordingly, with strenuous effort he stopped inhalation and exhalation through his mouth, nose and ears as before. When he did so, terrible pains arose in his head, just as if a strong man put a tough leather strap around his head as head-band, and then that man twisted it with a stick to tighten it up.

Still again, it occurred to him: “What if I were still to go on developing the appāṇaka jhāna!”

Accordingly, with strenuous effort he stopped inhalation and exhalation through his mouth, nose and ears as before. Thereupon, violent winds carved up his belly, as if a clever butcher or his apprentice carves up an ox’s belly with a sharp knife, even so plentiful air pierced his belly.

Once more, it occurred to him: “What if I were still to go on developing the appāṇaka jhāna!”

Accordingly, with strenuous effort he stopped inhalation and exhalation through his mouth, nose and ears as before. When he did so, the whole of his body suffered from a violent burning ḍāharoga, ‘burning disease’, just as if two strong men had seized a weaker man by both arms and were roasting him over a pit of live coals.

Thus, each time he cultivated the appāṇaka jhāna harder and harder, his effort kept strenuously arising. So was his mindfulness established and unperturbed. However, due to the painful effort his whole body was overwrought and uncalm. Although such painful feelings arose in him, his willingness to pursue the struggle remained unflinching.

His whole body was afflicted with heat so intense that while he was walking, he fell down fainting into a sitting posture. At that time, the devas who saw him falling down in this manner said: “Samaṇa Gotama is dead.” Other devas said: “Samaṇa Gotama is not dead, but he is dying.” Still other devas said: “Samaṇa Gotama is neither dead nor dying. Samaṇa Gotama is an Arahant, a Worthy One, for such is the way in which an Arahant abides.”

The Practice of Taking Little Food

After he fainted for a few moments, his consciousness recovered. So did his energy and mindfulness. He then took long in-breaths and out-breaths for several times in order to make his body a bit fresh. Afterwards, he rose and went to his seat under a tree. At that moment, he thought: “What if I were to practise complete abstinence from food!”

Thereupon, some devas approached him and said: “O noble samaṇa, do not practise complete abstinence from food! If you entirely cut off food, we shall inject divine food through your pores; with that food you will be sustained.”

Having heard what the devas would do to him, the Bodhisatta thought: “If I decide not to take food at all, and these devas were to inject divine food through my pores, and I am sustained thereby, then I shall be lying.” So he refused them, saying: “There is no need.”

Then it occurred to him such thought: “It would be good if I take food little by little for one day’s meal, say, a handful of bean soup, or a handful of grain soup, or a handful of lentil soup, or a handful of pea soup!”

And as he did so, his body gradually became thinner and thinner and reached a state of extreme emaciation. Due to lack of nourishment, the joints in his body and limbs protruded like the joints of knot-grasses or bulrushes (the grass or creeper called Āsītika and Kāḷa). His hips became like a camel’s hooves, and the anus was depressed; his spine stood forth like a string of big beads; as the flesh between his ribs sunk down, the ribs jutted out like the rafters of an old house; his eyeballs sunk far down in their sockets, just like two stars seen in a deep well; the skin of his head shrivelled and withered as a green gourd shrivelled and withered in the wind and sun.

If he touched his belly’s skin, he would touch his backbone too; and if he touched his backbone, he would touch his belly’s skin, too; and so his belly’s skin cleaved to his backbone due to lack of sustenance. When he was squatting to pass excreta, just one or two hardened balls the size of betel nuts were discharged with difficulty; and the urine also did not come out at all as there was not enough liquid food in the belly to turn into urine; so weak was his body that in doing thus, he toppled and fell down on the very spot with his face downwards. If he rubbed his limbs with his hands in order to soothe his body, the body-hairs which were rotten at the root fell away from his body due to under-nourishment from the flesh and blood.

At that time, the people who saw him said: “Samaṇa Gotama is of black complexion.” Others said: “Samaṇa Gotama is not black, his complexion is brown.” Some others said: “Samaṇa Gotama is neither black nor brown, his complexion is tawny.” So much had the bright yellow colour of his complexion deteriorated through eating so little.

One day, when he was walking up and down, once again he fainted, falling down with his face downward due to his body being afflicted by unbearable heat and not having enough nourishment. The people residing near the Uruvelā Forest knew that the Bodhisatta had hardly eaten anything for many days. At that time, a shepherd boy happened to pass by the place where the Bodhisatta fell down. He surmised that the

Bodhisatta was about to die because he had fasted too much. The shepherd boy immediately approached him and tried to wake him up. After the Bodhisatta was conscious again, the shepherd boy put the Bodhisatta’s head on his lap and fed him with goat’s milk. The Bodhisatta conveyed his gratefulness to shepherd boy and blessed him for his health and happiness.

Subjugating the Ten Armies of Māra (Dasa Māra Senā)

After six years, the Bodhisatta came to a critical stage; he was almost on the verge of death. However, he was still intent on the highest exertion (padhāna) by repeatedly developing the appāṇaka jhāna in the Uruvelā Forest near the Nerañjarā River.

Reading this situation, Namuci immediately approached him with a pretense of goodwill and pity, saying: “O noble prince, now you have become very thin; you have lost the glory of your body; much deteriorated is your body; your death is coming very close; only one against one thousand is the chance of your remaining alive. Live, O oble prince! Life is the better way. If you live long, you can perform meritorious deeds. You can lead a holy life and make sacrificial rites, and thus much merit you could gain. What is the use of this austerity practice? Hard to bear is this old path! Difficult to achieve is your goal! And without certainty is this practice! Indeed, it is not feasible to tread along such a way!”

In replying to Māra’s enticement, the Bodhisatta boldly said thus: “O Evil One, you, who always bind up sentient beings in the cycle of saṁsāra, you who always hinder sentient beings from their liberation; you have come here only for your own benefit.”

“I do not need even an iota of merit which leads to the cycle of suffering. Māra, only to those who are yearning for such merit, may you allure them thus.”

“Firm is my faith (saddhā) that I shall surely realise Nibbāna soon. Exuberant is my perseverance (viriya), capable of burning into ash the grassy rubbish of defilements. Incomparable is my wisdom (paññā), able to crush the rocky mountain of dark ignorance (avijjā) into pieces. Great is my mindfulness (sati), which leads me to become a Buddha, free from heedlessness. Unshaken is my concentration (samādhi), like Mount Meru, which does not sway in a storm.”

“O Māra, this wind in my body, caused by my exertion in developing the appāṇaka jhāna, could dry up the streams of the Gaṅgā, Yamunā, Aciravatī, Sarabhū, and Mahī Rivers. So while I am thus striving, why would it not be capable of drying up the little blood in me, whose mind has been directed to Nibbāna?”

“If the blood dries up, then the bile, the phlegm, the urine and nutritive elements dry up; and so will the flesh be certainly exhausted. But although the blood, the bile, the phlegm, the urine and the flesh in me are all gone in this way, my mind becomes even clearer; so do my mindfulness, my wisdom, and my concentration become even more developed and steadfast.”

“Though I am experiencing the utmost pain, though my whole body has dried up to the point of almost emitting flames, and though I am thereby thoroughly exhausted, my mind is never deviated by sensual lust. O Māra, what you see is the purity and uprightness of the incomparable man, who has fulfilled the Perfections.”

“Your first army is sense-desires (kāma). The second is aversion for holy life (arati). The third is hunger and thirst (khuppīpāsā). The fourth is craving (taṇhā). The fifth is sloth and torpor (thīna-middha), while fear (bhīru) lines up as the sixth. Doubt (vicikicchā) is the seventh. The eighth is malice, paired with obstinacy (makkha-thambha). The ninth is gain ((lābha), fame (siloka), honour (sakkāra). The tenth is extolling of oneself (attukkaṁsana) and denigrating others (paravambhana).

“Namuci, these are your ten armies which, by force, prevent the liberation of humans, devas and brahmās from the rounds of suffering. None but the brave, who possess great faith, will, energy and wisdom, can conquer them. This victory will bring about the bliss of the Path, Fruition and Nibbāna.”

“I wear muñja grass as a token that I would not retreat. It will be shameful, ruinous, and disreputable if I have to withdraw from the battle and be defeated by you and remain alive in this world. It is far better to die in the battle field than to concede defeat to your force.”

“In this world, there are ascetics and brahmins who went to the battle field of kilesa, but without strength they are overpowered by your tenfold army. They are like those who, without light, happen to have entered into darkness. They neither know nor tread the path of the virtuous.”

“O Māra, though you have arrayed your armies on all side, not even the slightest fear I have. Here, I go forth to fight you. You shall not drive me from my position. Your armies—which the world, with all its gods, cannot conquer—I shall now destroy with my wisdom, just as a stone breaks a raw clay pot.”

On hearing the valiant words thus spoken by the Bodhisatta, Māra departed from that place, unable to utter a word in reply.

Considering Another Way to Enlightenment

In one afternoon, the Bodhisatta reflected that he revived and felt better—after fainting on the previous day—thanks to the goat’s milk given by the shepherd boy. Else, he might have died. When he was reflecting thus, a group of singing girls, on their way to the city, crossed nearby the place where he was meditating. While walking, they were singing: “…if we tuned the lute’s strings too loose, it would not

produce sound. If we tuned the strings too tight, they would break apart. If the strings were tuned neither too loose nor too tight, the lute would sound sweet.”

His heart was deeply moved by the verses sung by the girls. He had indulged too much in sensual pleasures with all the luxuries when he was still living in the palace. Just as if the lute’s strings were tuned too loose, even so Enlightenment could not be realised through self-indulgence. And also, he had practised asceticism so strictly

that he was nearly dead. Just as if the lute’s strings were tuned too tight, even so Enlightenment could not be attained through self-mortification.

It was about the first waxing day of Vesākha, 588 B.C., when it occurred to the Bodhisatta thus: “In their practice of austerity, the ascetics or brahmins of the past could have gone through only this much pain and hardship at most; they could not have gone through more hardship than what I am enduring. So is it the same with the ascetics or brahmins of the future, and those of the present. But by this strenuous practice of self-mortification, I have attained no distinction higher than the human state, worthy of the noble ones’ knowledge and vision. Might there be another way to Enlightenment?”

Then, he recollected that when he was child, on the auspicious day of “Royal Ploughing Festival” performed by his father King Suddhodana he had been left by his royal attendants. At that time, he sat under the cool shade of a rose-apple tree; he was quite secluded from sensual desires and from unwholesome things. Then, he developed the ānāpāna bhāvanā and attained the first rūpāvacara jhāna, accompanied with thinking and exploring, with happiness and pleasure born of seclusion. Thereupon, he recognised: “Well, this is the way to Enlightenment.”

He further reflected: “Why should I be afraid of such pleasure? It is a bliss which arises purely from renunciation (nekkhamma) and is entirely detached from sensual pleasures. I am certainly not afraid of the jhānic bliss of the ānāpāna bhāvanā”

Then again, he continued to reflect: “It is impossible to develop and get such attainment of the ānāpāna bhāvanā with a body so emaciated.

It would be good if I eat some solid food, coarse food, such as boiled rice and bread to revive my emaciated body before I endeavour in this practice.”

Having considered thus, from then on the Bodhisatta went on alms-round to the market town of Senāni and ate every morning. By doing so, he sustained his withered and emaciated body. Within two or three days, he regained his strength, and the major physical characteristics of a Mahāpurisa—which had disappeared at the time of

practising dukkaracariya—reappeared distinctly.

The Group of Five Ascetics Left the Bodhisatta

The five ascetics, who were attending upon the Bodhisatta for six years with great hopes, had been thinking: “Whatever truth which the Bodhisatta has realised, he will impart it to us.” But now, when they saw the Bodhisatta changing his method by taking whatever coarse food offered to him, they became disgusted with him, grumbling: “The Bodhisatta has become self-indulgent; he has given up the struggle and reverted to luxury.”

Thereafter, the five ascetics left him and went to Migadāya, the Deer Park, in Isipatana, near Bārāṇasī (Benares). When the attendant ascetics had abandoned him, the Bodhisatta lived a solitary life in the Uruvelā Forest. Though their presence during his great struggle was helpful, but he was not discouraged of being alone now; instead it was advantageous to him. He gained a considerable degree of solitude

conducive to attaining extraordinary progress and strengthening his mental concentration.

The Bodhisatta engaged in dukkaracariya not only for days or months, but for six long years consecutively. So severe and strict was his practice that his muscles and sinews shrivelled, his blood dried up, and his eyes sunk owing to lack of nourishment; and the golden colour of his skin was blackened owing to the heat produced in his body. Thus, what one could see was only bones and skin—a living skeleton. No other ascetics could surpass him in the practice of asceticism. And

although he experienced all those difficulties and pains, he never bewailed them. Even more extraordinary was his face, which was skinny but always looked smiling, as though he was not afflicted by any pain.

During that hard time, there had never come up to his mind such a thought: “This long have I exerted all my strength and ability; and this long have I endured all, even the severest pain, but omniscience have I not attained! Useless indeed what I have done! I shall go back to my palace! The throne of Kapilavatthu is mine as I am the only inheritor, and I will surely be a Universal Monarch as I have the characteristics of a Mahāpurisa. In the palace, I will live happily with my beautiful wife-princess Yasodharā, and also with my mother, father, and eighty thousand relatives, who are still alive. I can enjoy all the luxuries like a deva. Why should I waste my time here in the forest?” There had never been the slightest thought in him for an easy and self-indulging life.

※ 画像やテキストの無断使用はご遠慮ください。/ All rights reserved.

アシン・クサラダンマ長老

1966年11月21日、インドネシア中部のジャワ州テマングン生まれ。中国系インドネシア人。テマングンは近くに3000メートル級の山々が聳え、山々に囲まれた小さな町。世界遺産のボロブドゥール寺院やディエン高原など観光地にも2,3時間で行ける比較的涼しい土地という。インドネシア・バンドゥンのパラヤンガン大学経済学部(経営学専攻)卒業後、首都ジャカルタのプラセトエイヤ・モレヤ経済ビジネス・スクールで財政学を修め、修士号を取得して卒業後、2年弱、民間企業勤務。1998年インドネシア・テーラワーダ(上座)仏教サンガで沙弥出家し、見習い僧に。詳しく見る

奥田 昭則

1949年徳島県生まれ。日本テーラワーダ仏教協会会員。東京大学仏文科卒。毎日新聞記者として奈良、広島、神戸の各支局、大阪本社の社会部、学芸部、神戸支局編集委員などを経て大阪本社編集局編集委員。1982年の1年間米国の地方紙で研修遊学。2017年ミャンマーに渡り、比丘出家。詳しく見る

※ 画像やテキストの無断使用はご遠慮ください。

All rights reserved.